How Did Attitudes Toward Poverty And Crime Change In The Antebellum Era?

Slavery in the Antebellum Catamenia

Slavery was a class of forced labor existing equally a legal institution from the colonial period until the mid-nineteenth century.

Learning Objectives

Describe how slavery became the foundational economic institution in the antebellum Due south

Primal Takeaways

Key Points

- Slavery was integral to the agronomical economies of the South, and thus to the nation's prosperity, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- By 1804, most Northern states abolished slavery, and the federal authorities prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory and banned the external slave trade, spurred by abolitionism movements that denounced slavery as sinful and antithetical to the principles of the nation.

- Treatment of slaves was mostly characterized by brutality, deposition, and inhumanity; whippings, executions, and rapes were commonplace. Slaves resisted via rebellions, noncompliance, and flight.

- Slaveholders and those with vested interests in the plantation economic system had a strong influence on national politics, forcing compromises over the preservation and extension of slavery from the time of the drafting of the Constitution through the 1850s.

- Over the form of the Civil War, the Union made abolition a goal of the war effort. They succeeded, and all slaves were freed, without bounty for their owners, with the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Key Terms

- Mason-Dixon line: Also known as "Mason and Dixon's Line," a boundary surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Stonemason and Jeremiah Dixon in the resolution of a edge dispute betwixt British colonies in colonial America.

- manumission: Release from slavery; freedom.

- Dred Scott: An African-American slave in the The states who unsuccessfully sued for his freedom and that of his wife and their ii daughters in the Dred Scott five. Sandford case of 1857, popularly known as the "Dred Scott Decision."

Slavery existed in the Us as a legal institution from the early colonial period. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, an estimated 12 one thousand thousand Africans were shipped as slaves to the Americas. Of these, an estimated 645,000 were brought to what is now the United states of america. According to the 1860 U.South. Census, the slave population in the United States had grown to iv million.

Race was a critical element of chattel slavery. Slaves were of African descent and children of slaves became slaves themselves. Freedom was only possible via granting of manumission by a slave's owner, a practise that was frequently regulated and sometimes prohibited by law, or by the slave running abroad, which was both dangerous and illegal.

The handling of slaves in the The states varied depending on conditions, time, and place, but was generally characterized by brutality, degradation, and inhumanity. Slaves were denied basic didactics, and in some cases, prohibited from convening for religious gatherings, in order to prevent potential escape or rebellion. Punishment was meted out in response to perceived disobedience or infractions, but also every bit a means for a master or overseer to assert potency. Slaves were punished past existence whipped, shackled, hanged, beaten, burned, mutilated, branded, and imprisoned. Slave women were at loftier risk for rape and sexual abuse, a exercise partially rooted in the patriarchal Southern culture of the era that perceived all women, black or white, as property or chattel. Many slaves fought back and some died resisting this sort of treatment, though some managed to escape to non- slave states and Canada, aided past the Underground Railroad.

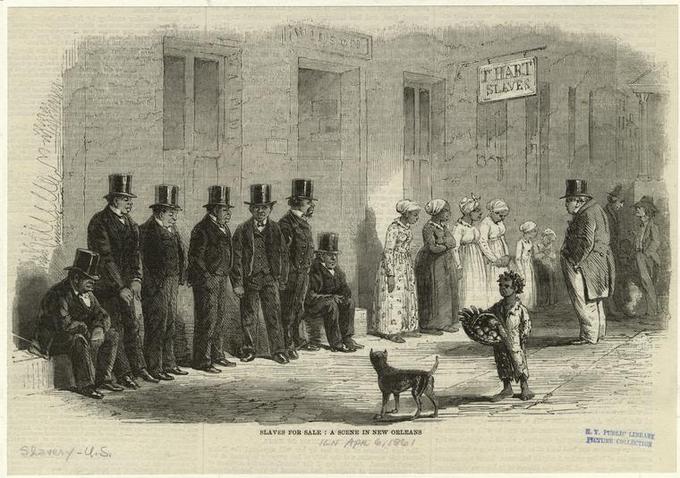

"Slaves for Auction: A Scene in New Orleans": This image depicts slaves for auction.

While some slaves worked in urban areas every bit domestic servants, most labored on plantations or large farms where their owners took advantage of skilful quality soil and a temperate climate to mass produce cash crops such as rice, tobacco, sugar, indigo, and cotton. In small operations, slaves worked side by side with their owners; on big plantations, they were directed by white paid overseers.

The labor-intensive agricultural economies of the S during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were dependent upon the connected institution of slavery. Because Northern industries depended upon the crops produced in the Southward, it seemed to many that the nation'southward prosperity was as well tied to the institution. The invention of the cotton wool gin in the late eighteenth century had revitalized cotton production in the South and Southwest, further increasing demand for slaves. Slaveholders of the South exercised strong influence over U.Southward. politics, and many presidents were slaveholders. However, by 1804, all states n of the Mason-Dixon Line had either abolished slavery outright or passed laws for the gradual abolition of slavery based upon abolition movements that viewed the exercise of slavery every bit unethical, antithetical to the cadre principles of the United States, and detrimental to the rights of all gratis persons. Accordingly, the nation was polarized along the Mason-Dixon Line.

Slave States and Complimentary States: Animation showing which areas of the United states did and did not allow slavery between 1789 and Lincoln's inauguration in 1861.

Past the 1850s, the Southward was vigorously defending slavery and its continued expansion into new U.Due south. territories. Compromises were attempted and failed, and in 1861, xi slave states bankrupt away to form the Confederate States of America, leading to the American Civil War.

In 1862, the federal government made abolition of slavery a war goal. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln freed slaves in the rebellious Southern states via the Emancipation Proclamation. By Dec 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment took upshot, permanently abolishing slavery throughout the entire The states with no compensation for the quondam slaves' owners. The areas afflicted included border states such every bit Kentucky, which was home to approximately 50,000 slaves at the time, as well as Native American tribal territories.

The Proslavery Statement

Proponents of slavery argued that it protected slaves, masters, and society equally a whole.

Learning Objectives

Identify the key tenets of the proslavery argument

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Southern slaveholders' proslavery arguments defended the interests of the plantation owners against attempts by abolitionists, lower classes, and non-whites to institute a more equal social structure.

- Southern proslavery theorists argued that the class of landless poor was easily manipulated and thus could destabilize society as a whole.

- The "mudsill theory" of Henry James Hammond argued that there must be a lower course for the upper classes to residuum upon.

- "Positive good" theorists, such as John C. Calhoun, believed that slavery, with its strict and unchanging social hierarchy, made for a more stable society than that of the Northern states where wage laborers of various backgrounds engaged actively in autonomous politics.

- William Joseph Harper was a leading proponent of the notion that slavery was non only a necessary evil, just a positive social good, and his "Memoir on Slavery" reinforced this idea.

Primal Terms

- apologist: One who speaks or writes in defense of a faith, a cause, or an establishment.

- Mudsill theory: A sociological idea that there must exist, and e'er has been, a lower course for the upper classes to rest upon; the name is derived from the lowest threshold that supports the foundation for a building.

From the late 1830s through the early 1860s, the proslavery argument was at its strongest, in part due to the increasing visibility of the small simply vocal abolitionist motion, and in part due to Nat Turner 'south rebellion in 1831. Among those nigh famous for propagating the proslavery argument were James Henry Hammond, John C. Calhoun, and William Joseph Harper. The famous "Mudsill Speech" (1858) of James Henry Hammond articulated the proslavery political statement when the ideology was at its most mature.

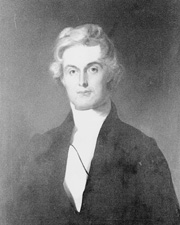

James Henry Hammond: James Henry Hammond's 1858 "Mudsill Voice communication" argued that slavery would eliminate social ills by eliminating the class of landless poor.

These proslavery theorists championed a form-sensitive view of American antebellum social club. They felt that the bane of many past societies was the existence of a form of landless poor. Southern proslavery theorists felt that this course of landless poor was inherently transient and easily manipulated, and as such, ofttimes destabilized order as a whole. Thus, the greatest threat to republic was seen every bit coming from class warfare that destabilized a nation'southward economy, gild, and government, and threatened the peaceful and harmonious implementation of laws.

This "mudsill theory" supposed that in that location must be, and has e'er been, a lower class for the upper classes to rest upon. (The mudsill is the lowest layer that supports the foundation of a edifice.) James Henry Hammond, a wealthy Southern plantation owner, described this theory to justify what he saw as the willingness of the non-whites to perform menial work: Their labor enabled the college classes to move culture forward. In this view, any efforts toward class or racial equality ran counter to this theory and therefore ran counter to civilisation itself.

Southern proslavery theorists asserted that slavery prevented any such attempted movement toward equality by elevating all free people to the condition of "citizen" and removing the landless poor (the "mudsill") from the political process entirely. That is, those who would most threaten the democratic society'south economic stability and political harmony were not immune to undermine it because they were not allowed to participate in it. In the mindset of proslavery men, therefore, slavery protected the common good of slaves, masters, and society as a whole.

In 1837, John C. Calhoun gave a speech communication in the U.S. Senate advocating the "positive skillful" theory of slavery, declaring that slavery was, "instead of an evil, a skillful—a positive good." Theorists of "positive skilful" believed that slavery, with its strict and unchanging social hierarchy, made for a more stable society than that of the Northern states, where wage laborers of various backgrounds engaged actively in democratic politics.

These arguments asserted the rights of the propertied elite against what were perceived to exist threats from abolitionists, lower classes, and not-whites to gain higher standards of living. John C. Calhoun and other pre-Civil War Democrats used these theories in their proslavery rhetoric as they struggled to maintain their grip on the Southern economy. They saw the abolition of slavery as a threat to their new, powerful Southern market, a marketplace that revolved near entirely around the plantation system and was supported by the apply of black slavery.

William Joseph Harper

William Joseph Harper (1790–1847) was a jurist, political leader, and social and political theorist from Southward Carolina. He is best remembered as an early representative of proslavery thought. His "Memoir on Slavery," first given equally a lecture in 1838, established Harper as a leading proponent of the notion that slavery was non in fact a necessary evil only rather a positive social expert.

Senator William Harper: Senator William Harper is best remembered as an early representative of proslavery idea. He argued that slavery was not in fact a necessary evil but rather a positive social good.

Harper advanced several philosophical, racial, and economic arguments on behalf of slavery, but his central idea was that "slavery anticipates the benefits of civilisation and retards the evils of culture." Harper'south cess of other nations around the world confirmed this point of view. Non-slaveholding civilizations in northern climates, such every bit Peachy Britain, were fractured by inequality, political radicalism, and other dangers. Meanwhile, non-slaveholding civilizations in more than southerly areas, such as Spain, Italy, and United mexican states, were rapidly slipping into "degeneracy and barbarism." Simply the slaveholding Southern Usa, Brazil, and Cuba were seen every bit making "favorable progress."

Every bit did nearly every other defender of slavery before 1840, Harper nominally conceded that slavery, at an abstruse level, did constitute a sort of (necessary) moral evil. Withal his strong, positive emphasis on the social and economical benefits of the institution separate him from the weaker apologists for slavery of earlier decades.

Plain Folk of the Old South

The "Obviously Folk of the Old South" were a middling class of white farmers who occupied a social rung between rich planters and poor whites.

Learning Objectives

Identify the "Plain Folk of the Old South"

Central Takeaways

Cardinal Points

- The "Plain Folk of the Quondam South" owned land, were subsistence farmers, and endemic few or no slaves.

- These farmers often are referred to every bit "yeomen," a term that emphasizes an independent political spirit and economic self-reliance.

- Historians accept long debated the social, economic, and political roles of Southern classes.

- "Plainly Folk" supported secession to defend their families, homes, notions of freedom, and behavior in racial hierarchies.

- Historians contend that a distinctive Southern political ideology blended localism, white supremacy, and Jeffersonian ideas of agrarian republicanism.

Key Terms

- yeoman farmer: A free man who endemic his own farm, especially during the Elizabethan era through the seventeenth century.

- agrarian: A person who advocates the political interests of working farmers.

- secession: The act of seceding from the marriage.

The "Plain Folk of the Sometime South" were white subsistence farmers who occupied a social rung between rich planters and poor whites in the Southern United States earlier the Civil War. These farmers tended to settle in backcountry, and most of them were Scotch-Irish American and English language American or a mixture thereof. They owned land, generally did non raise commodity crops, and owned few or no slaves. Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democrats preferred to refer to these farmers as "yeomen" because the term emphasized an independent political spirit and economic self-reliance.

Historians accept long debated how large this group was and how much influence its members exerted on Southern politics in the antebellum period, particularly why and to what extent these farmers were willing to support secession despite their typically not being slaveholders themselves. Frederick Police force Olmsted (a Northerner who traveled throughout and wrote about the 1850s S) and historians such as William E. Dodd and Ulrich B. Phillips considered common Southerners as minor players in Southern antebellum social, economic, and political life. Twentieth-century romantic portrayals of the antebellum South, especially Margaret Mitchell'south novelGone with the Wind (1937) and the 1939 picture adaptation, by and large ignored the part yeomen played. The nostalgic view of the S emphasized the aristocracy planter class of wealth and refinement who controlled large plantations and numerous slaves.

Gone with the Air current

Twentieth-century romantic portrayals of the antebellum South, such as Margaret Mitchell's novel Gone with the Current of air (1937) and the 1939 film adaptation, mostly ignored the role of yeomen.

The major challenge to the view of planter dominance came from historian Frank Lawrence Owsley'due south volume, Plainly Folk of the Onetime Due south (1949). His work ignited a long historiographical contend. Patently Folk argued that yeoman farmers played a significant part in Southern society during this era rather than existence sidelined past a dominant aristocratic planter class. The religion, language, and culture of these common people comprised a democratic "Plain Folk" society. Critics say Owsley overemphasized the size of the Southern landholding middle class and disregarded a large course of poor whites who owned neither land nor slaves. Owsley believed that shared economic interests united Southern farmers; critics suggest the vast difference in economic classes between the elite and subsistence farmers meant they did non have the same values or outlook.

In his report of Edgefield Canton, South Carolina, Orville Vernon Burton classifies white social club into the poor, the yeoman centre class, and the aristocracy. A clear line demarcated the elite, only according to Burton, the line between poor and yeoman was less distinct. Stephanie McCurry argues that yeomen were clearly distinguished from poor whites past their ownership of real belongings (i.eastward., land). Yeomen were "self-working farmers," singled-out from the elite considering they physically labored on their land alongside whatever slaves they owned. Planters with numerous slaves had work that was essentially managerial, and oft they supervised an overseer rather than the slaves themselves.

Nevertheless, the very presence of slaves throughout the American South fostered white unity despite economic disparities. In a speech before the U.S. Senate in 1858, South Carolina senator and planter, James Henry Hammond, demonstrated this logic by arguing that slaves comprised, "the very mud-sill of lodge," or a bottom supportive layer to a class system delineated across racial lines.

Though Southern society was dominated by a planter elite, "Patently Folk" supported secession to defend their families, homes, notions of liberty, and behavior in racial hierarchies. Historians argue that a distinctive Southern political ideology blended localism, white supremacy, and Jeffersonian ideas of agrarian republicanism.

Licenses and Attributions

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/the-antebellum-south/

Posted by: cookrowasoul1987.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Attitudes Toward Poverty And Crime Change In The Antebellum Era?"

Post a Comment